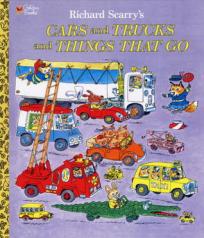

Once upon a time, fresh out of college and a little wide-eyed, I had a boyfriend who had grown up on Richard Scarry. That boyfriend’s world overflowed with Anglophiles and intellectuals and Scarry —in a twist of misdirected intimidation — acquired a certain aura of kid-lit-mystique for me. (I assumed that these unknown classics were English, too, which of course made them that much more fabulous.)

In fact, Scarry (1919-1994) was a prolific American author-illustrator, and his books are nothing if not accessible. His full and detailed illustrations in the Busytown books and others offer up a simple sort of engagement that young children adore: innumerable details and visual story fragments that let kids look and search and spy and name — and where they can’t name, ask. Kids spend their days doing the same thing out in the real world, noticing and engaging in visual play with whatever grabs their attention. But books like Scarry’s add the dimension of a beloved adult’s lap.

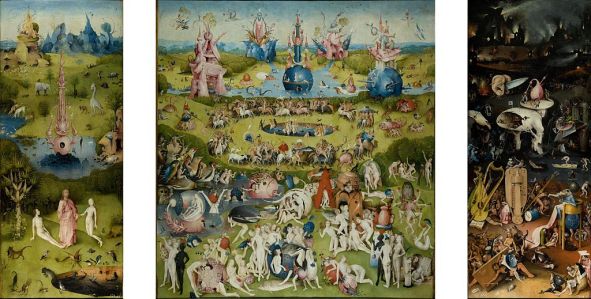

Scarry’s picture books are essentially beginner-wimmelbilderbuch or wimmelbooks. German author-illustrator Hans Jurgen Press (1926-2002) coined the term in the mid 20th century and it translates loosely as “teeming picture book”; the format clearly owes a debt to the 15th and 16th century paintings of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Brueghel the Elder. But Press’s books incorporated the element of the hunt, making the visual meander more goal-oriented: instead of the eye simply wandering as it would in staring out the side of a stroller or a car window (or at a Bosch painting), it has something to find in these books’ considered and dense illustrations.

Martin Hanford’s Where’s Waldo books, Jean Marzollo and Walter Wick’s I Spy series and Graeme Base’s Animalia, The Water Hole and others all fit under the heading of ‘wimmelbook’ too.

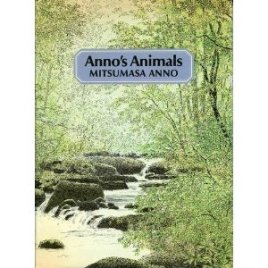

Mitsumasa Anno, in the wimmelbooks he created, gave new twists to the form as he moved past pure density of imagery. In Anno’s Animals, he masterfully turned the game on its head, hiding prey in landscapes that he drew to seem anything but full. And, in Anno’s Counting Book, his detail-rich illustrations play with number and one to one correspondence, introducing a new, mathematical dimension to the hunt.

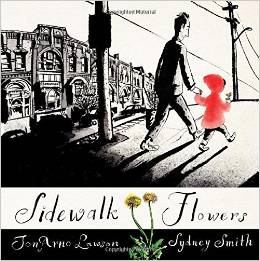

Writing recently about JonArno Lawson and Syndey Smith’s new book Sidewalk Flowers (Groundwood Books), Maria Popova describes the book in terms that connect to the poignancy wimmelbooks have for this particular historical moment too. A wordless tale, Sidewalk Flowers follows a girl as she walks through the city holding her father’s hand; throughout, her attention to details on the street contrasts with her father’s chronic digital distraction. Popova dubs the book “a magnificent modern manifesto for the everyday art of noticing in a culture that rips the soul asunder with the dual demands of distraction and efficiency.“

Kids excel at noticing, being observant and tuning in. Adults: not so much. And these habits of mind are precisely what wimmelbooks demand.

A wimmelbook with more contemporary styling, Lotta Nieminem and Jenny Broom’s Walk This World was published in 2013 by Big Picture Press, a new-ish partnership between Templar Co. Ltd. (UK & Australia) and Candlewick (US & Canada). Big Picture’s introductory video features Bosch and frames Big Picture’s undertaking as being about creating “illustrated books for people who like to look at pictures and discover something new each time.” It should be fun to see what else Big Picture Press publishes and what new twists and turns the form takes as other authors and illustrators experiment. Maybe they will turn out a few more ‘modern manifestos’ or, at the very least, create some stellar new encouragements for kids (and their adults) to focus for more than a few minutes on images that aren’t moving and don’t require electricity.